Disinformation Is a Global Risk. So Why Are We Still Treating It Like a Tech Problem?

The UN’s 2024 Global Risk Report ranks mis- and disinformation as a top global threat. UN Development Coordination Office Chief of Communications and Results Reporting, Carolina G. Azevedo, explores why youth-led, UN-backed efforts in Kenya and Costa Rica may hold lessons for building trust in the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

In a world shaken by conflict, climate shocks and inequality, some of the most dangerous threats may also be the least visible. Disinformation is one of them.

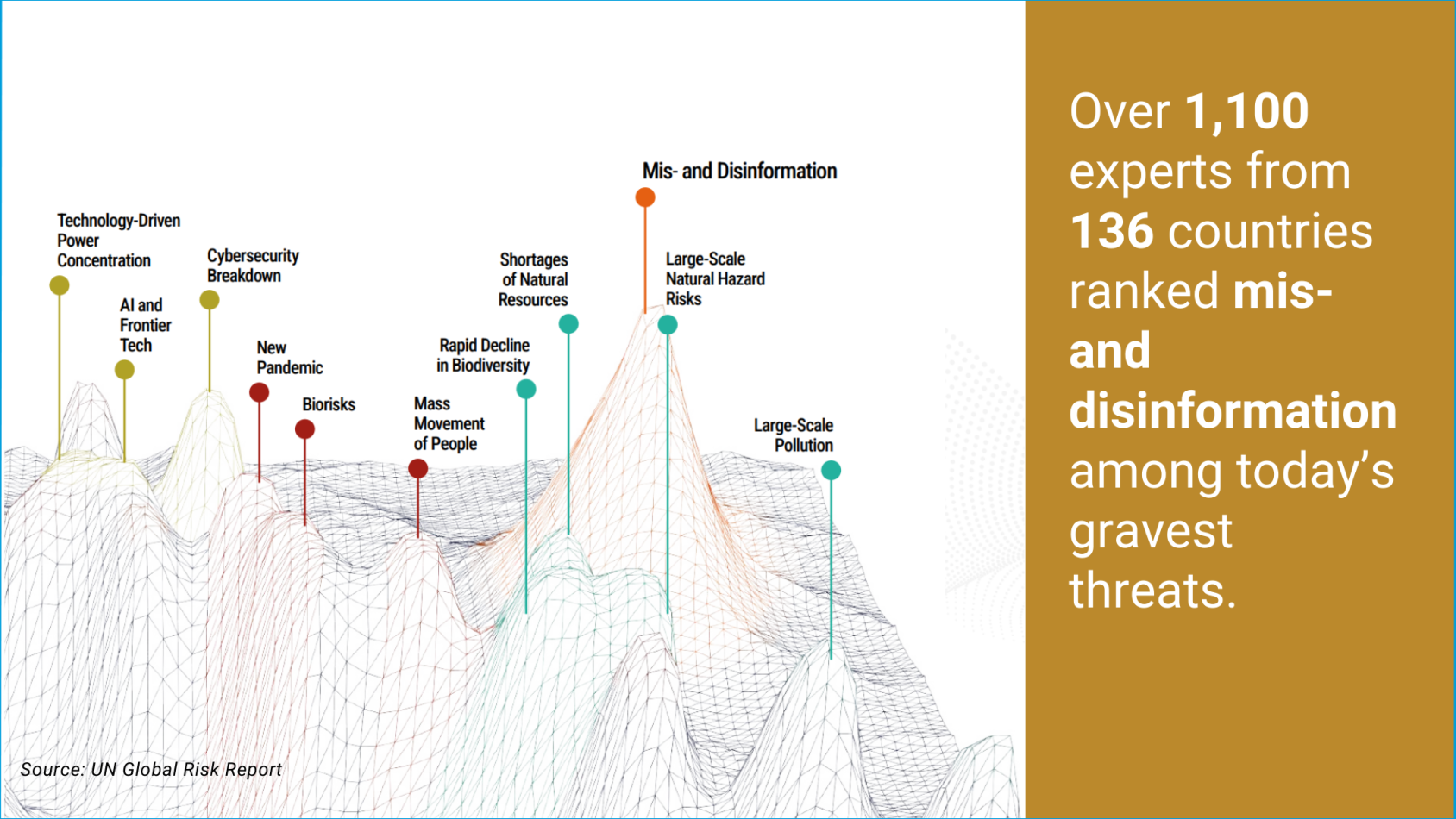

According to the recently launched UN Global Risk Report 2024, mis- and disinformation is not only a top global threat—it’s the one countries feel least prepared to address. Over 1,100 experts from 136 countries ranked it among the gravest risks, and more than 80 per cent said it’s already happening.

This isn’t just a communications issue—it’s a crisis of trust. Tackling it means protecting communities from harm while upholding freedom of expression and other human rights.

Disinformation can unravel the threads that hold societies together. In settings with increased instability, it can tip societies into violence. It can also corrode the norms of debate and science-backed evidence that societies take for granted.

A personal glimpse

My 85-year-old mother recently shared with her granddaughter a video of a baby elephant moving a tree. My 12-year-old daughter glanced over and said gently: “Grandma… it’s adorable. But that’s not real. It’s AI.”

My mom was crestfallen—not because it was harmful, but because she felt tricked.

That moment captured a growing divide, including in generational and digital literacy, recognizing what’s real and what isn’t.

It's not just about fake videos

A fake elephant may seem harmless, but the systems generating synthetic content are growing more sophisticated—and potentially more dangerous too. They can:

- Incite hate and violence

- Undermine health and science

- Erode trust, including in elections

- Discredit climate action and other government-led efforts to accelerate the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

And they are evolving faster than regulation can catch up.

A system not broken—but built this way

The real challenge is structural. The information ecosystem wasn’t designed for truth or safety. It was designed for engagement—and that also includes hate. Falsehoods travel faster than facts. And moderation? Inconsistent, especially in non-English contexts.

We are not just confronting a broken system. This isn’t safety-by-design. It’s addiction-by-design.

In my recent research at Princeton University, I explored why content moderation is a wicked problem—one with no clear boundaries, no single owner, and no easy fix.

As I wrote in Governing the Hydra: Why AI Alone Won’t Solve Content Moderation, tackling harmful content post by post is not only inefficient—it also risks curbing fundamental human rights like freedom of expression. And it doesn’t solve the problem. It’s like cutting off the mythical Hydra’s head: more grow back, often in darker corners.

The UN recognized this complexity early through several strategies and policies:

- Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech (2019)

- Global Principles for Information Integrity (2024)

- The Global Digital Compact (2024), part of the Pact for the Future

In important complementary ways, these frameworks stress that digital and information integrity, transparency, accountability and human rights must be central in governing today’s digital spaces.

As the Secretary-General warned, “Hate speech is a precursor to atrocity crimes.” And it spreads like wildfire.

So how do we respond in a do-no-harm approach?

A serious response must go beyond takedowns and fact-checks. It means:

- Designing for safety from the start

- Elevating youth leadership

- Embedding digital integrity and literacy into policy

- Bridging global principles with local action

Kenya: Youth-led digital peacebuilding

Ahead of recent elections, the Government of Kenya asked the Resident Coordinator, leading the UN team, to address a surge in online hate speech—especially on platforms popular with youth. Instead of simply monitoring the situation, they partnered with youth-led networks, civil society, tech innovators, and government counterparts to co-create a solution grounded in community trust.

With support from the Government of Germany and the UN Peacebuilding Fund, young analysts used AI tools trained in local dialects to map harmful narratives in real time. But the effort didn’t stop there: it engaged journalists, faith leaders, and influencers, many of them youth themselves, to interrupt disinformation before it could spiral into violence.

This was not just content moderation. It was “digital peacebuilding”—led by young changemakers and enabled by national partners and UN support. The result? Faster responses, deeper civic engagement, and a powerful narrative shift: from youth as disinformation targets to agents of democratic resilience.

Costa Rica: Building trust in the digital age

In Costa Rica, the Resident Coordinator, leading the UN team, brought together government institutions, civil society, academia, and the private sector to tackle online misinformation linked to sustainable development and hate speech.

Using AI-powered analysis of information flows and disinformation networks, the UN team backed culturally tailored, evidence-based strategies. They helped surface root causes, boost public awareness, and rebuild trust in institutions and multilateral action.

Even in a noisy and fragmented online environment, these whole-of-society efforts suggest that progress toward digital integrity is possible—when partners come together, with the UN as a trusted convener and catalyst for innovation.

A call to act—now

Tackling disinformation isn’t just a tech challenge—it’s a test of our collective resolve. From building digital trust to elevating local voices, it will take all of us: governments, communities, businesses, platforms, and, most importantly, people.

It’s a wicked problem.

But it’s one we can confront—together.

This blog was written by UN Development Coordination Office Chief of Communications and Results Reporting, Carolina G. Azevedo